The Fleeting Persistence of Hopelessness

(A Comment on Why American Teens Are So Sad)

A recent essay in The Atlantic titled Why American Teens Are So Sad starts with alarming news:

The United States is experiencing an extreme teenage mental-health crisis. From 2009 to 2021, the share of American high-school students who say they feel “persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness” rose from 26 percent to 44 percent, according to a new CDC study.

The notion that nearly half of U.S. teens have been in a state of constant desperation lately is reinforced by a graph labeled Percent of High-School Students Feeling Persistently Sad or Hopeless that displays the rate climbing up to 44.2% in 2021:

Note: The Atlantic mislabeled 2009 as 2004 and at least two data points are incorrect (Overall rate in 2015 and 2017) -- but these errors are not relevant to this critique.

The problem is that it is not true.

The Actual Measure

What The Atlantic article does not mention is the fact that the question asked if a student ever felt 'sad or hopeless' for 2 weeks within the entire past year.

If you ask students if they ever felt hopeless, you may get close to 100% of them replying 'yes' -- and yet a newspaper headline screaming Nearly All Kids Feel Hopeless! would be utterly wrong.

It is similar here: we have no reason to believe that, over the last decade, at least one third of students at any given time felt sad or hopeless, as implied by the graph provided by The Atlantic.

In fact we have a solid indicator that, during this time period, the vast majority of students felt "very" or "pretty" happy at any given time and only up to 20% felt "not too happy" -- meaning those feeling outright sad or hopeless, not to mention persistently so, were always a far smaller subset (see Happiness Survey in Notes below).

Mental Health

The Atlantic essay uses the 'sadness' graph as its primary indicator of teenage mental health trend and this is yet another area where the graph can be extremely misleading.

The problem with this is that the survey reveals mainly the prevalence of 'ordinary' trauma -- the kind that is experienced by nearly all of us in youth, even though the event itself may be extraordinary at individual level.

Such events need not indicate mental health disorders. There is nothing mentally wrong with a teenager who experiences persistent sadness for two weeks after, say, a grandparent dies. In fact the passivity induced by such sadness may be a protective mechanism granted by evolution -- think of a prehistoric youth deeply disturbed by the death of a relative: the kid would be safer inactive for a while instead of going on hunting or gathering missions.

Without additional information it is impossible to tell if kids experience such periods of sadness because they are less able to cope with adversity or because ordinary adversity is actually increasing (such as during the pandemic).

Why it Matters

It turns out that teenage happiness has indeed been declining during the past decade and that so has the mental health of adolescents (see Notes).

The readers may then ask: do the above objections really matter much?

They do matter.

Besides the general principle that misleading communication in science is always potentially problematic and thus unwelcome, there are two areas in which this particular misinformation can be especially detrimental to our understanding of adolescent mental health.

The first problem is that we may end up reaching unsubstantiated conclusions about the effects of the pandemic -- such as that mental health of kids deteriorated greatly, given the roughly 25% increase in students being 'persistently sad or hopeless' from 2019 to 2021. In reality, the very survey used by The Atlantic to paint such a bleak picture of the pandemic effects also points to a contrary conclusion since there was no significant increase in the number of teens reporting suicide attempts within the first year of the pandemic -- and this agrees with CDC data on the number of actual teen suicides during that period. To evaluate the consequences of the pandemic for mental health, we need data on outright disorders such as clinical or chronic depression, number of teenage suicides, and so on.

The second problem is that exaggerations may mislead us in our quest for answers. The current state of adolescent mental health may seem unprecedented if one follows news media coverage and yet indicators ranging from happiness to suicide show that the current situation is comparable to the mental health state of teens in the early 1990s -- and that it is much better if we consider aggression and drug abuse as part of overall mental health.

Could it be that child depression and suicide has been increasing partly in proportion with the increasing share of parenting done by the very generation whose own adolescence was marked by extremely poor mental health? I have yet to see any psychologists explore this possibility in depth, perhaps because they have developed a blind spot due to the frequent portrayals of our youth as far more mentally troubled than any previous generations -- including those of the very academicians now offering various explanations as to why kids nowadays are supposedly so fragile.

Notes

The 'Sadness' Question: this item comes from the biannual Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) of high school students and its full text is as follows:

During the past 12 months, did you ever feel so sad or hopeless almost every day for two weeks or more in a row that you stopped doing some usual activities?

Graph Errors: Note that the large jump in overall rate from 2015 to 2017 does not make sense in view of very small increases in both the male and female rates. The actual overall rate should be 29.9 in 2015 and 31.5 in 2017. Other data points on The Atlantic graph might be in error too -- I did not check them all.

Pandemic Data: The YRBSS administration for 2021 was postponed and its results were not yet released as far as I know. The 2021 data in The Atlantic is evidently taken from the Adolescent Behaviors and Experiences Survey (ABES) that used a subset of the same questions as YRBSS (including those on sadness and on suicide attempts). The survey, however, was answered by students remotely from home instead of directly at school, and for this and other reasons caution is required when comparing the 2021 ABES results with those of 2019 YRBSS.

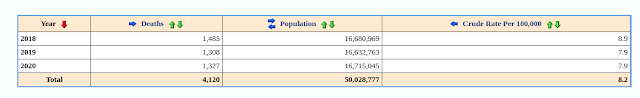

Suicides: the 2020 rate of suicide for ages 14-17 (roughly the students covered by YRBSS and ABES) remained unchanged from the 2019 rate (which itself was below the 2018 rate) per CDC data:

Happiness Survey: the only long-term tracking of teenage happiness in the U.S. seems to be the one administered by the annual Monitoring the Future (MtF) survey via the following question:

Taking all things together, how would you say things are these days--would you say you're very happy, pretty happy, or not too happy these days?

The portion of HS seniors answering "not too happy" was 18.3% back in 1992 -- a share that was not surpassed until 2019 (19.7%) and 2020 (21.6%). Although once-a-year survey of feelings is not a highly robust measure (the timing of the questioning may have a strong impact), there is a clear trend recently with gains every single year since 2013 (12.3%).

Derek Thompson: I have no reason to think that staff writer Derek Thompson, the author of The Atlantic essay, was deliberately or unscrupulously biased -- in fact I am convinced he tried to be as accurate as possible. It is, however, easy to stumble when one is not already deeply familiar with the subject of adolescent mental health.

Proposed Explanations: the plausibility and sufficiency of the explanations offered by Thompson for the declines in teenage mental health are beyond the scope of this critique. I will, however, note that I think Thompson is right in believing there is more than one major factor involved in these trends. In fact I suspect that, based on the complexity of adolescent mental health trends, there has been a mixture of long-term and short-term causes without any one factor being a clear dominant force.

Links

Why American Teens Are So Sad (The Atlantic):

<https://www.theatlantic.com/newsletters/archive/2022/04/american-teens-sadness-depression-anxiety/629524/>

Adolescent Mental Health: for evidence that the mental health of teens has been deteriorating, see a public document maintained by Jon Haidt at <https://docs.google.com/document/d/1diMvsMeRphUH7E6D1d_J7R6WbDdgnzFHDHPx9HXzR5o>

Adolescent Suicide: For info specifically on the recent doubling of child and adolescent suicide see my Youth Suicide Rise project at <https://theshoresofacademia.blogspot.com/2019/11/youth-suicide-rise-articles-index.html>

YRBSS Data: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/index.htm

ABES Data: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/abes.htm

MtF Data: https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/web/NAHDAP/series/35

Good point about the prehistoric youth and the dead grandparents.

ReplyDeleteAdelaide Dupont

Thank you. I wrote more on the evolutionary origins of incapacitating sadness -- and why it would impact girls more than boys -- in Blinded by Gender: A Comment on The Dangerous Experiment on Teen Girls.

ReplyDelete