Childhood Trauma: Adult Fatal Injuries

Note: this is part of the Youth Suicide Rise project.

We discovered a strong correlation between youth suicide rates and cumulative risk of childhood exposure to suicide (as measured by all-age suicide rates), and we speculated this to be only one of a group of childhood trauma factors that have been increasing.

What other such factors could be involved?

Let us first examine fatal injury deaths among adults.

Adult Fatal Injuries

Fatal injuries have increased greatly among 'parental' adults aged 30-59:

The increase since the start of the millennium was nearly 60% -- indicating that kids nowadays are more than half as likely to be exposed to an unexpected death of a parent or a similarly close adult.

Interestingly the Great Recession (2008-2009) did not lead to increases in fatal injuries among middle-aged adults -- if anything it may have stalled the ongoing trends.

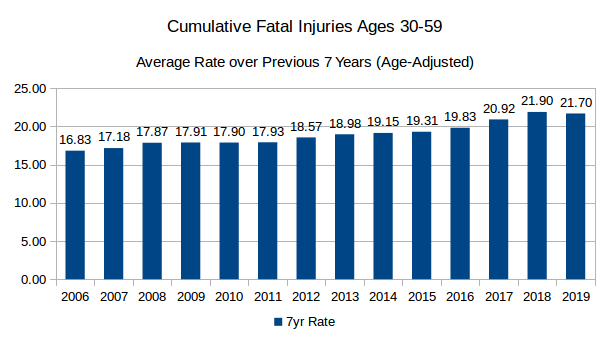

The cumulative 7-year rate has has a similarly increasing pattern:

Why did fatal injuries rise so much for this age group?

To see this, it is best to look at rates by major types of fatal injuries:

We can see that even though suicide rose by nearly 40%, the main contributor has been drug overdose: it added about 280 deaths per million while suicide added only 50 and homicide 10.

In fact drug overdoses more than quadrupled since 1999 and more than doubled since 2007.

If we count only accidents -- thus ignoring suicide and homicide -- then the remarkable development is that in 2017 the majority of all accidental deaths among middle-aged adults was due to drug overdoses.

We can also look at the percentages:

The increases in drug overdoses were so dominant that the share of deaths declined for all other types of injuries, even suicide.

Deaths of Abandonment

A parental death due to suicide or drug overdose may be more damaging to a child psychologically than other deaths because the child may feel the parent did not sufficiently care about the child -- as if the despair or the addiction were more important than the child.

If we sum up suicides and drug overdoses among middle-aged adults, the development was as follows:

1999: 213 deaths per million

2007: 323 deaths per million (50% increase)

2017: 530 deaths per million (65% increase since 2007, 150% increase since 1999)

Cumulative exposure over preceding 7 years:

Thus a teen in 2019 had nearly double the likelihood of having previously experienced a childhood trauma due to an 'abandonment' death of a parent or a similarly close adult.

Conclusion:

Childhood exposure to unexpected death trauma likely increased considerably; this is in part due to more suicides among adults but mainly due to a massive increase of drug overdose deaths among middle-aged adults.

Notes:

In 2018 there was a small decline in drug overdoses while suicide still increased slightly.

It is possible that some drug overdoses were undetected suicides; on the other hand, it is possible that some suicides were committed due to despair over addiction. In our approach the differences in intent and motivation do not matter much since all such deaths may result in a similar trauma for a child feeling abandoned by such an adult.

We will examine young adults separately; we concentrated on middle-aged adults under the assumptions that this 'parental' group affects children the most among adults.

Another task is to look at youth suicide correlations with exposure to various types of adult fatalities (besides suicide) since the 1980s.

We should also keep in mind that all the data here is at aggregate levels; we have no correlations at the individual level. The possibility of ecological fallacy thus applies, but this is not yet an issue since we are merely searching for plausible theories -- not jumping to conclusions about causes.