Female Share of Youth Suicides

Note: this is part of the Youth Suicide Rise project.

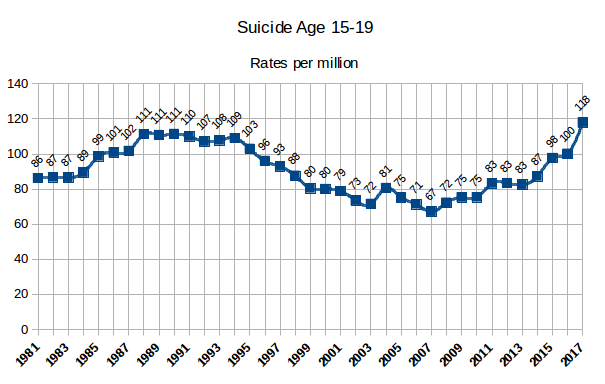

We saw in The Rise: Sex Ratio Trend that the ratio between suicides by boys versus girls has been (mostly) declining since at least the start of the millennium.

Perhaps the most intuitive view of this trend is to look at the female share of youth suicide over the years:

Note that the 3-year (tween and teen child) and 5-year (youth) Moving Average green line values are displayed at the endpoints and so any 'green line' trend implicates all the previous 3 or 5 years.

From the graphs it is clear that the trend of increasing female share of child or youth suicides started about a decade before 2008.

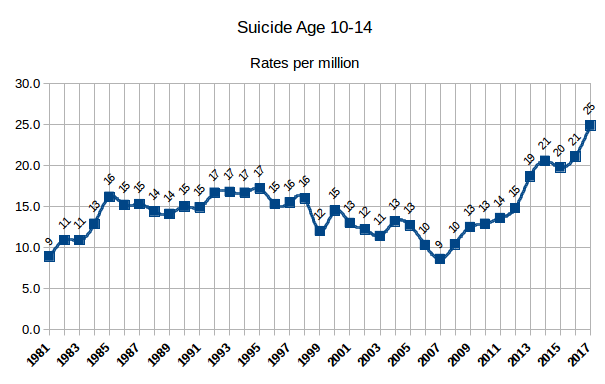

Let us examine with particular care the 10-14 age group -- the one where suicide gains among girls are proportionally the greatest -- by looking at its 3-year moving average:

With 3-year accumulation it is especially clear that the most recent rise in female share of tween suicides -- even discounting the strong reversal in 2017 -- is not exceptional.

We can identify 3 instances of a rise followed by a momentary decrease:

From 1999-2001 to 2004-2006: 1.7 percentage points per year

From 2005-2007 to 2008-2010: 1.6 percentage points per year

From 2010-2012 to 2014-2016: 1.9 percentage points per year

The recent rise of the female share of youth suicide is not particularly stronger than the trend established in the early part of the millennium. This is true even of tween girls, whose suicide rates rose the fastest.

Let us examine with particular care the 10-14 age group -- the one where suicide gains among girls are proportionally the greatest -- by looking at its 3-year moving average:

With 3-year accumulation it is especially clear that the most recent rise in female share of tween suicides -- even discounting the strong reversal in 2017 -- is not exceptional.

We can identify 3 instances of a rise followed by a momentary decrease:

From 1999-2001 to 2004-2006: 1.7 percentage points per year

From 2005-2007 to 2008-2010: 1.6 percentage points per year

From 2010-2012 to 2014-2016: 1.9 percentage points per year

Summary

The recent rise of the female share of youth suicide is not particularly stronger than the trend established in the early part of the millennium. This is true even of tween girls, whose suicide rates rose the fastest.

Note:

This issue is important partly because some researchers and journalists may mistakenly assume that any factor primarily responsible for the rising child suicide must be also responsible for the concurrently rising female share of child suicide -- and thus be affecting (proportionally) girls much more than boys. This need not be so.

Technical note:

All share values were computed from suicide rates rather than from suicide counts.

The rates used to calculate the female share of suicides for age group 10-14 as well as 15-19 were age-adjusted (as calculated by CDC based on the 2000 demographic data). The rates used in the teen (13-17) group calculations were crude rates (the WISQARS tool is inconsistent in this regard). The difference should be insignificant (demographic shift are very small and slow).