The Importance of Being Inquisitive

JAMA Research Letter on Pediatric SA/SI ED Encounters

A year ago, April 2019, JAMA-P published a Research Letter titled Suicidal Attempts and Ideation Among Children and Adolescents in US Emergency Departments, 2007-2015

by Burstein et al. Its authors estimated suicide-related visits to U.S. emergency departments by

children between 2007 and 2015. The paper included the following assertion:

"Notably, 43.1% of SA/SI visits were for children aged 5 to younger than 11 years".

Note: The authors actually meant to write "younger than 12 years" -- and indeed the Table included with the paper had the age category defined as 5 to < 12. This minor error is not the subject of this post. The SA/SI in the paper stands for Suicide Attempts and Suicidal Ideation, respectively.

The 43% assertion was widely and prominently repeated in the media at the time by news outlets including CNN and USA Today.

HuffPost quoted the lead author as follows:

“These numbers are very alarming,” study author Dr. Brett Burstein, an emergency department physician at the Montreal Children’s Hospital of the McGill University Health Centre in Montreal, told HuffPost. “Not only was there doubling over the study period; we also found in this broad, nationally representative sample that there is a high proportion — more than had been previously identified — that are presenting at a very young age group.”

Besides media exposure, the Burstein et al. paper accumulated 28 scientific citations in less than a year.

More

recently, an article titled What Happened to American Childhood? in The Atlantic also mentioned the 43% result: "Children’s emergency-room visits for suicide attempts or

suicidal ideation rose from 580,000 in 2007 to 1.1 million in 2015; 43

percent of those visits were by children younger than 11."

Doubts

Sonia Livingstone, Professor of Social Psychology at the London School of Economics, read the "43 percent of those visits were by children younger than 11" assertion in The Atlantic and expressed doubts about it on an email list.

David Finkelhor, Director of the Crimes against Children Research Center, seconded Sonia's disbelief.

I had to agree with Sonia and David, since the 43% assertion seems implausible in view of statistics related to suicide.

Children

under 12 constitute only 3% of child suicides, according to CDC Fatal Injury data, and suicides by children under the age of 9 are cumulatively in single digits annually. The suicide rates for the 5-11 age cohorts range from 1000 to 100 times lower than teen child rates.

Even

if we assume that the SA/SI ED visits by young children concerned mainly

suicidal ideation, the problem remains since per Burstein et al. the SI without SA visits constituted only one eight of all SA/SI visits. Furthermore,

middle-school YRBS (Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance) results indicate that suicidal

ideation is less common among preteens than it is among teens.

Simply

put, the numbers do not add up -- there is no credible manner in which

the 43% result could be compatible with other statistics related to suicidal conduct.

The Error

Burstein et al. used National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS) samples data for their analysis. I

downloaded the relevant data files for 2007-2015 and, contrary to the authors, found nothing

indicating so high a share of pediatric SA/SI visits to ED by kids so young.

The difference between my calculations and those of the JAMA authors was severe: I found that children aged 5-11 constituted 7% of child SA/SI ED encounters in the NHAMCS sample -- 3% of SA and 11% of SI visits. The 7% share is far below the 43% share reported by the authors.

The lead author, Dr. Burstein, is currently preoccupied with fighting the pandemic. Despite being extremely busy, he kindly sent me some STATA code fragments.

The STATA code

indicates that the authors mistakenly presumed an implied E prefix in the values of the DIAG fields (diagnoses), and consequently counted ICD-9 codes 950-959 (Injury other

and unspecified) as if it was ICD-9 codes E950-E959 (Suicide and Intentional Self-injury).

In the end, the Burstein et al. results were more about pediatric head-and-face injuries, which dominate

the 959 category, than about suicide.

Sanity Checks and Suicidal Babies

It is not troubling that a researcher makes a mistake parsing a data file.

It is a bit troubling, however, that a mistaken result gets through the peer review process despite having to be at least somewhat surprising to anyone remotely familiar with the topic.

Unexpected results, even if not viewed as outright implausible, should be subject to heightened scrutiny.

In the JAMA case, reviewers could have asked for more details on the ages 5-11 group.

For example, the paper gives separate SA and SI counts for pediatrics patients, but not for the 5-11 subgroup. Had reviewers asked for this, they would likely have received the strange result that the share of this young group is much higher for SA than for SI, since based on the code fragments sent to me, the 95/E95 mistake inflated only the SA share of this young group.

The reviewers could have also asked how frequent are SA/SI ED visits for 5-8 year-old patients, to see if there is any decline with declining age. This should have led to the next question: does the methodology produce any SA/SI ED visits for 0-4 year-old patients?

Again, based on the code fragments, the erroneous method would have identified many children aged 0-4 as being suicidal -- indeed many less than a year old (since head-and-face injuries are being mistaken for suicidal attempts).

The existence of such 'suicidal babies' in the results would have revealed beyond doubt a serious problem with the Burstein et al. data analysis.

In general, while looking a step deeper or wider may not catch mistakes where the effects are subtle or limited, it does tend to catch mistakes where the effects are absurd or massive. Such 'sanity checks' are necessary, especially when an unexpected result is being reported.

The Importance of Being Inquisitive

Only Sonia Livingstone noticed an implausibility that so many others have missed for a year.

The 43% assertion coverage in news media must have been seen by thousands of professionals familiar with child suicide issues, hundreds of child psychologists, and dozens of experts on suicide.

The 28 current citations of the Burstein et al. letter are in articles written by a cumulative total of over 100 authors.

And yet no one before Sonia noticed the dubious nature of the 43% assertion -- or if they did, then failed to take steps toward its correction.

The reality is that overly dubious or outright implausible results may survive indefinitely as established facts despite wide media and academia exposure. That is the most troubling aspect of this story.

Until the scientific process is improved to better minimize such occurrences, we will have to depend on the acuity of people like Sonia.

Notes:

It seems the authors also over-counted suicidal ideation, since their STATA code indicates checking only the first 3 characters instead of all 5 in the V6284 code for SI.

One consequence of the errors is that the SA/SI visits estimate for the ages 5-11 group was incorrect by a factor of 30: their estimate was 3.16 millions instead of 100 thousand per my calculation. Estimates for older children were also inflated, though to a lesser degree.

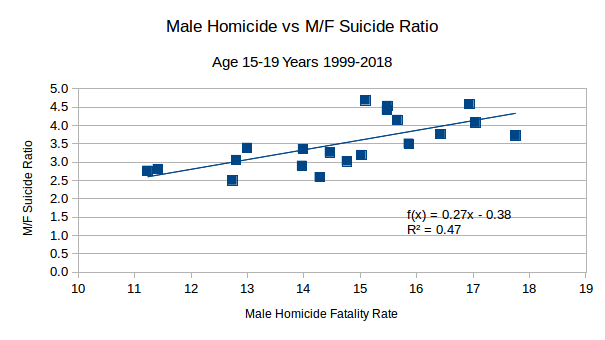

Furthermore, the authors reported more SA/SI visits by boys than by girls, which was surprising, given that girls are about twice as likely to report suicide attempts as boys. In my results, girls are clear majorities: roughly 65% for SA and 60% for SI.

I did try to reproduce the erroneous analysis indicated by the STATA code fragments, and the results were nearly identical to those reported by the authors -- thus confirming the STATA coding was indeed the problem.

Warning: my own calculations were not checked by anyone else -- and certainly not peer reviewed -- so please consider them tentative.

I will update this post with info regarding correction or withdrawal of the JAMA-P Research Letter once the authors have the time to address the matter (likely after the pandemic crisis ends).

(The reason I mention possible withdrawal is that lower visit counts for SA/SI children translate into high margins of error, especially for time trend analysis, since these calculations are made from small samples -- it is therefore unclear if the authors will be able to salvage enough statistically significant results.)